Cabbage

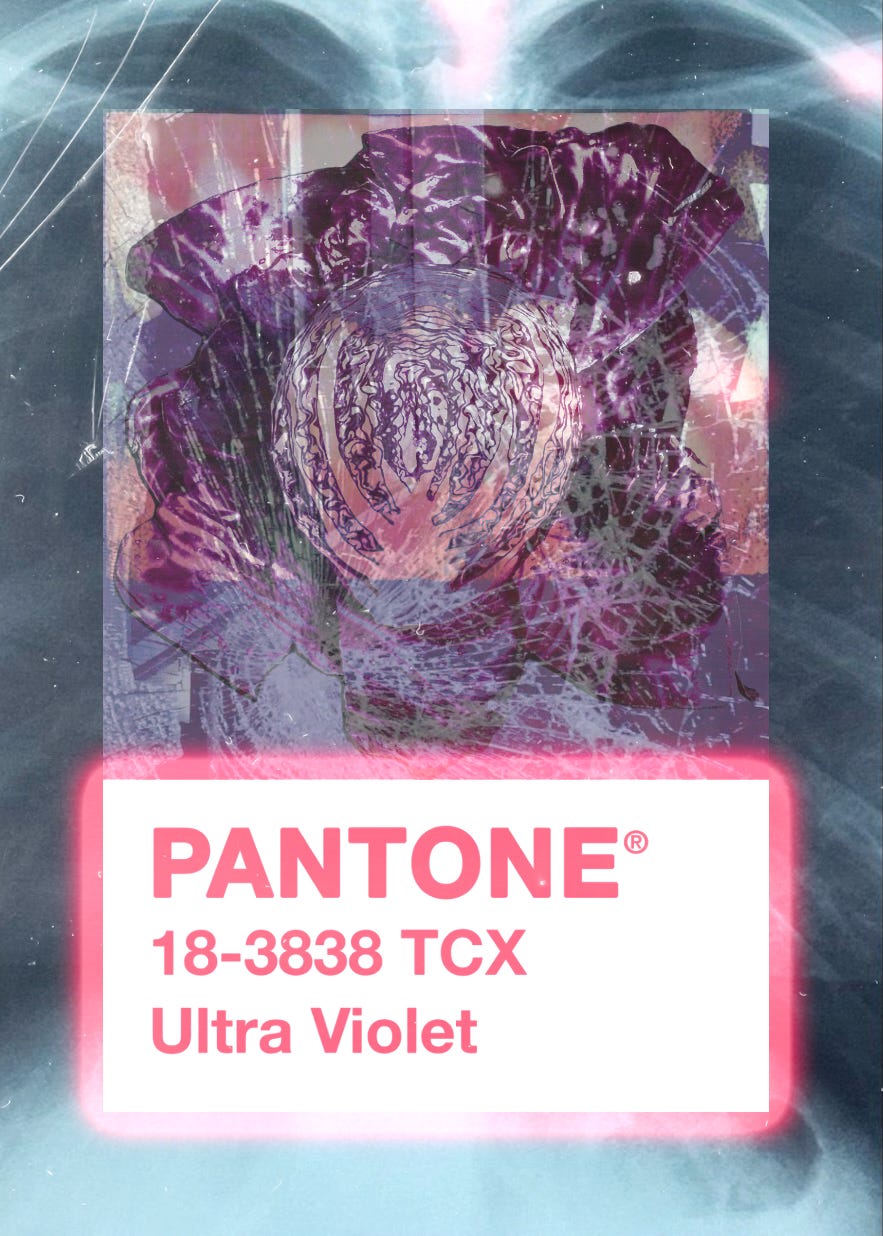

All the violence inside you becomes violet in me.

The events and dialogue in this piece are written from memory and are therefore extremely fallible. The names and identifying details of many individuals and places have been changed—and in some cases, separate entities (including people) have been condensed into one. This essay is a biased recollection of my experiences, which are emotionally true but, like all things remembered, not to be taken as fact. Consider this a work of autofiction.

Thank you kat for editing.

In 2015, I started my short tenure at the preparatory boarding school that my (then very-much-alive) brother considered his gateway to the “real world.” Nate’s admission and subsequent graduation opened him up to opportunities that a child raised under the oppressive hold of low income and the isolation of a rural environment would not otherwise be able to grasp: His Ivy League degree, for one, and all the fine things that follow you when you obtain something like that—worldly interests, refined tastes, prestige, the envy-tinted respect of all outsiders. Money, most of all.

I am not sure what similarities he saw between us when he pushed me to apply for admission decades later. We were raised in separate centuries under different circumstances. By the time I was born, he had already graduated college. My mother began raising him in her late teenage years, and she was in her forties when I came into the world. Even the landscape we were raised in fell victim to the sweeping hand of time—landmarks in our rural hometown that he once knew and loved were flattened by neglect, overgrown with kudzu and tagged into oblivion.

Later, after we had both run far away from that place, it would fill with new life. Empty storefronts would become occupied with cafés where you could order green juice and get it, expecting no laughter. Craft breweries would emerge, along with ugly apartment complexes that sell luxury living to college professors and other temporary residents. There seemed to be a polished exterior on the place I remember finding so rough and cruel. I’m sure it’s still in there, somewhere, underneath that pearlescent veneer.

When I made the trip from Maine back to Mt. Vernon for his memorial, I could no longer recognize the landscape I once knew more intimately than anywhere else on Earth. I wondered, if he could have witnessed it for what it was now, would his mind have changed? Was it finally a part of the real world?

It was only my fifth day in Arizona. I’d gotten off the bus one stop too early, and I ended up walking half a mile in hundred degree heat, sweating off my makeup and letting my feet blister in red ballet flats. I was crying out of frustration, adding to the ruddy complexion the sun had given me. My mom had been so nervous about this, and I brushed her off. Earlier in the week she’d wanted to ride the bus with me, make sure I knew exactly what my route was. I told her I’d be fine. She didn’t believe me.

Still, I was comically early. I just wanted to make a good impression. It was my first degree-utilizing job after college—I’d moved across the country for it. I wanted to make sure I did it right. But here I was, 45 minutes early with a terrible case of swamp ass and hair so weighed down with sweat that it looked as if it had never been styled at all.

When I realized I was the only person there, I went to the bathroom to try to resuscitate the version of myself that I left back in Maine. She was thinner, prettier, funnier. She had a slightly more cohesive sense of style. She ‘lit up a room,’ I’d been told. I rifled through my bag—a tote my mom picked out for me at World Market only a few days earlier. It had a Tarot card printed on it. The World, or maybe The Wheel. It was the only one left, I remember that much. She was excited she’d found it, and I was excited she knew me well enough to choose it.

I reapplied my lipstick, an unflattering shade of hot pink I’d so obviously never tried before. I wiped the sweat off my face, trying not to disturb my newly shaped eyebrows. I even cooled my armpits with the hand drier so the stiff, conservative shirt I’d just bought wouldn’t have visible wet marks when I raised my arms. I checked my teeth, whitened with a purple toothpaste I’d let sit too long and now the enamel had a chalk-like quality. I lifted my lips with my fingers to see if it had gotten any better. It hadn’t, and then I heard noise from outside—voices clanging like cutlery sinking to the bottom of an industrial sink. I could hear conversations clearly through the door, and my stomach turned with the doorknob as I made my way out of the bathroom.

The other teachers were talking and laughing, exchanging stories from the summer over gluten-free bagels and underripe plums and other foods low enough on the glycemic index to be considered suitable for real adults who wear things like linen dresses and wide-brimmed hats.

“The new English teacher,” a woman so tiny that, sans glasses, I would have mistaken her for a child embraced me. Without hesitation and without any reason, I hugged back. “You’re from Maine, right?”

“I just moved from there, yeah,” I answered. An unnatural silence followed. I couldn’t make conversation the way I used to. I don’t know when that happened. Maybe I was dehydrated.

“Well, welcome to Arizona. How long have you been here?”

“Not quite a week,” I smiled out of the side of my mouth. I hated my teeth, but wanted to seem friendly, and just ended up looking like an ugly Katie Holmes.

“Well,” she answered after a moment. “I hope you’re loving it. I’m Feather, I teach Latin. We’ll be sharing a classroom.” I noticed her eyes travel from my hair down to my clothing. I wondered if my look was convincing. I called it my ‘teacher drag,’ because there truly was no other phrase that would suffice; everything, from my compression bra to my flowing pants, was self-obstructing performance. Feather’s gaze settled on my tattoos, and I knew I failed the pantomime.

“You look very young,” she said. “Are you very young?”

“By teacher standards, yes, probably.” The sweat on my body had cooled on my skin, and it shocked me. I was no longer overheating. Strangely, I was cold. For the first time since I’d left the Northeast, I felt cold. It was an all-consuming frigidity, as if all the perspiration had hardened on my flesh and turned to ice. I wondered if I looked as stiff as I felt.

I’m sure I did, because Feather could tell I wasn’t quite listening to her anymore. She turned away and started fidgeting with the spread. I was later told she was the one who had set it out, and retroactively hoped she didn’t find it rude that I wasn’t eating.

You’re going to have a lot of fun, I remember my principal telling me when I was hired. The new teachers are all fun. Young people. You guys will have fun.

I believed her. And I was excited for it— a supercut of adulthood sold to me by Sex & the City flashed in my brain. I was stuck on this image of forming a core friend group; the kind where we might start a book club or have wine nights and listen to NPR or some bullshit like that. I thought this was the place I’d blossom into someone sophisticated and kind. I thought I’d find myself made new and elevated. I thought I might meet a bridesmaid. Looking around now at these people, people I thought would be my people, the hairline fracture in that fantasy began to grow limbs.

Cabbage was looming over the others, and I do mean looming. They weren’t exactly unassuming: they were substantially taller than everyone else in the room; towered at least a foot over Feather. Their hair was longer than mine, watery-blonde and curly, separated into chunks by the scalp’s natural oils, which exposed the wetness and shine of their forehead. I couldn’t tell how old they were, couldn’t make any assumptions with even the softest outline of accuracy about what kind of person this was. They wore the clothes of a Floridian, a Republican, a recreational golfer—but stood with rounded shoulders, the way children do when they’ve grown into their height and aren’t yet sure what to make of it. We floated around each other. I pulled at loose fibers on my pants, they sipped hot coffee out of a Cincinnati Bengals glass meant for iced drinks.

“Are you from Ohio?” I asked. “I didn’t think I’d meet anyone else here—”

“I’m not from Ohio.” It was curt. I didn’t like the way they cut me off. I didn’t like the way their voice sounded muffled and loud all at once, like it came from the soft palate. But, as they spoke, they smiled with thin canines protruding from the rest of their mouth. It endeared them to me.

Quirks in their teeth. That was all it took.

My admission to boarding school marked the end of my ability to stay in the same state for longer than five years. I never should have been enrolled in the first place—everybody involved in my going there would probably agree with me now.

Nate pulled every string he could. He coached my admission interviews, used his legacy status to persuade the dean when I was waitlisted. And when I got off the waitlist, when we couldn’t pay the price of room and board, he told me that I could live with him and be a day student until I got a scholarship that would cover all of my expenses.

I didn’t want to be a day student. I wanted it all. I wanted the whole elite school experience: the tragic shit I’d seen in Dead Poets Society, the scandalous shit in Gossip Girl, the horrifying shit in Looking for Alaska. Like Esther Greenwood with her figs, and like Augustus Gloop’s great fall into that chocolate river, I suppose I always wanted more.

After an entire summer of combing through the internet’s swath of scholarships, I came up with the cash to live in the dorms with the other girls and was enrolled three weeks before classes started. I wouldn’t admit it at the time, but I always knew it was going to end badly. Even at 14, with limited knowledge of myself and the world at large, I knew that nothing good could come from the pressure of boarding school. But I also had a terrible feeling, for whatever reason, that if I stayed in Mt. Vernon, something worse would be waiting for me.

“You get very few chances to start over in this life,” Mr. Bee told the incoming freshmen at the evening orientation once we’d said goodbye to our parents and gotten settled into our rooms. “This is one of them. Go on, look around. These are the people with whom you will form the closest bonds of your life with. When you’re old, as old as me if you can imagine it, you’re going to want to remember these people.”

I did as instructed—turned my head to the left and right, tried to memorize the faces that would supposedly become more important than my own family, but my eyes drifted down to other details. A girl who looked more like a woman in a yellow bouclé top. A boy with the general demeanor of an infant wearing a Gucci belt to hold up his oversized khakis. Blonde highlights. Designer backpacks. Boat shoes.

I didn’t feel like this was somewhere I was going to thrive. Until this moment, I thought I might finally have the chance to become a ‘pretty girl’—my mom recently let me get my hair lightened at the ends, something that would have gotten me branded artsy and cool back at home, but now just made me look like I was too poor to have my roots done regularly.

“Now,” Bee said. “If you have a parent who teaches here, please stand up.” Around five kids stood up. I raised my hand. He gestured for me to speak, confused.

“Does a brother count?”

“Who’s your brother?” he asked

“Nate,” I said. “Uh, Jacklin.” He raised his eyebrows. I could read his mind: How old is Nate? How old are your parents? These were the same questions I’d been getting my entire life.

“Stand up, then.” Then, more quietly: “That guy’s my boss.”

And I stood, feeling like an imposter. I felt the eyes of the other children on me with the same confused expression as Bee.

“If you have any questions about campus,” Bee continued speaking to the group. “These folks should be your first contact. You should consider them a resource.”

The feeling that I’d intruded on something that I didn’t earn sank into my skin. I obviously did not live here. I didn’t know anything.

We sat back down. Bee paused for a moment, and the whole room was silent. I didn’t know the word for tinnitus, so I thought I could hear the air running through the walls.

“You are all in a very special position. Throughout the years, more students will join your class: new sophomores, new juniors, even new seniors. But you will always be the originals,” he smiled. “And in four short years, you will be the fourth year seniors. That’s something to be proud of.”

I swallowed hard, trying to clear away or flatten or dissolve the lump in my throat. I couldn’t imagine that. And I tried to: I saw a version of myself that had shed both my softness and my spirit; an older me who’d been steamrolled by her environment and made cruel by circumstance. I didn’t want it. I didn’t want any of it. But I was here now, with a wish—my wish—granted. And I couldn’t stop it from happening.

Cabbage invited me to go with them to a restaurant when the staff broke for lunch, and, with 13 dollars in my bank account, I agreed. They asked me what I was hungry for, and I told them something cheap.

Throughout the morning, I’d learned that they were in a band. I’d learned that it was a rock band, and that they’d toured the country for this rock band. I learned about their love of driving buses. I’d learned that they were from the Mid-Atlantic, but that they’ve lived in Arizona for a long time. I’d learned that they had friends, lots of them, and that their birthday was in a week. I learned they got fired from their last job—but that it was fine, that the school was corrupt, that they’d only given a too-hard test and that they were, by all measures, an “amazing teacher.” Now, I’d learn that they knew of the alleged best Chinese food in the city.

“I’ll drive,” they told me, and we walked out of the building. “My car is kind of messy though.”

I don’t know what I was expecting. Takeout cups and gum wrappers. Maybe vape cartridges or cigarette butts (I’d learn later that they hated smoking and hated smokers more-so—and they’d make me feel stupid for assuming otherwise).

I know what I wasn’t expecting: food so molded it was obscured in shape and clouding the Tupperware, piles of stained and wet clothes. Brown liquid settled in puddles on the backseats. The whole car smelt like mildew and fry grease.

We didn’t drive far, but Cabbage made sure to talk the whole time.

“Do you know anybody in the city?” They asked.

“I have one friend here who I went to college with.”

“Is she a teacher?”

“No. They work in…um. Rocks.”

“Ah,” Cabbage said, reversing into a parking spot. I didn’t like how fast they were doing it, but they had a command of the wheel that made me feel safe, even if that safety was only cosmetic. “Gem people. So you don’t have any friends here.”

“I wouldn’t say that,” I said.

“I would.”

We were seated within seconds. Besides the woman working both as hostess and waitress, there were no other people in the dining room.

Cabbage asked me what kind of music I liked. They asked me what my favorite movies were. They asked me innocuous questions in a salacious way. They hunched their shoulders to meet me at eye level, looked at me in a way that made me feel observed and ignored all at once.

“I’m an ox,” they pointed at the table, which had the Chinese zodiac printed on paper and pressed between two pieces of glass. “What’s yours?”

Suddenly, I felt embarrassed to be 23. Like a child listening in on an adult conversation. It was so odd—I’d spent the last year of college feeling wilted, and the following year working at McDonald’s feeling useless. I thought I’d aged out of being spectacular, too old to be wanted. And this ugly relationship with youth that I had only got uglier when we lost Nate.

Throughout all of my college years, I struggled with the horrible and soul-mangling fear that my window to be a charming ingénue was behind me (like that’s the worst thing that can happen to a woman) but after he died, I kept picturing myself dead at forty-five, too. I couldn’t decide whether it was an intrusive thought or a fantasy, and I really couldn’t decide whether or not I wanted to figure that out. I started retinol at 20. I ugly-cried over my cake on my 18th birthday, cried harder on every birthday since. When Olivia Rodrigo reached global stardom in 2021, and I realized that in a few years, all new popstars would be women younger than me, I panicked for days. Nate texted, months before he died, that he “hoped to be an old man some day,” and I also wanted that for him, but I couldn’t understand it at all.

Here, however, flooded by the overhead lighting and too illuminated to hide behind anything, I felt younger than I ever had. It was the same blend of shame and panic I felt at 15 when I snuck into a house party and met an LA-bound musician who asked me to record his producer tag. You’re perfect for it, he’d said. And for me. How old are you?

I found a passing moment of satisfaction in this urge to say I was older than I really was. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t miss this feeling.

“Guess,” I said.

They looked at the table for a long while before pointing at the rabbit.

“God, I wish. That’s so cute.”

“Horse?”

I shook my head, pressed my lips together.

“Jesus, just tell me.”

“It’s the snake,” I said.

I watched them locate the blurb on the menu, settle on the years, and then do the math in their head. 23.

“You know, the way I draw the line between Millennials and Zoomers is by how well they remember 9/11.”

“Well, I remember it quite well. I was nine months old. Very traumatizing.”

“When’s your birthday?”

“March ninth.”

“Six months,” Cabbage said. I looked at them, puzzled.

“You were six months old,” they repeated.

“Oh. Sorry.”

“You’re a Pisces, too,” they noted, like it was news to me—like I hadn’t gone into a sort of spiritual psychosis after my brother died where I spent months letting astrology apps dictate every life decision I ever made, including a few that led me to this restaurant, sitting in front of them with my hands clasped on the table.

“Yeah. I’m a Pisces sun. I have a double Virgo, too. My moon and rising.”

They scoffed, spit out a half-laughed “that’s crazy.” I didn’t understand what they meant by that, and I guess that feeling spread to my face, because they elaborated: “That’s just an awful line-up, and it makes so much sense that you’d have that chart and be an English teacher. I’m a Leo. The best sign. Obviously.”

I rolled my eyes. “You would say that.”

“You don’t know me,” they said, narrowing their eyes. “Yet.”

When we finished our food, and the waitress-slash-hostess brought the single check over, they covered it with their hand, pulled it close to their side of the table and took out an orange credit card.

“I got it.”

“Oh, I can—”

“You’ll get the next one,” Cabbage smiled. “We should head back.”

They held the door for me, and part of me was glad to have met someone so nice, but the deeper, truer observation that I couldn’t say aloud was that we had just been on a date that I wasn’t aware was happening until it had ended. I tried to silently work out in my head whether or not I felt guilty about that. I thought of my fiancée at home. I thought of how Cashmere would leave our bedroom every night to call her friend from grad school, sometimes for an hour or more. She’d talk about how he understood her in ways that she didn’t think possible—how in another life it was them, and not us. And I realized that I felt bad, but I couldn’t make myself feel any guilt.

At the end of the work day, they put their phone number in my contacts list and told me to text them my favorite album. At the time, it was Lime Cordiale’s 2017 release Permanent Vacation, but I wanted to look cool, so I sent them my second-favorite, Mulatu Astatke’s Ethiopiques Vol. 4.

“I’ll take you home if you want,” they said. “So you don’t need to take the bus.”

“No, it’s okay. I like the bus,” I said.

“Let me take you home.”

“Okay.”

This would become our rhythm: them asking to do something, me saying no. Them doing it anyway. That first lunch created a state we would later default to, and it would become as natural as breathing for me.

Later, at home, I Googled them. I found their Bandcamp, their Last.fm. I found articles about their music with pictures of them sporting a sharper jawline and less heaviness around their midsection. They dressed with more intention in these photos, had their hair pushed to one side instead of clinging to their scalp. Their eyes were brighter, expressions less muted.

I found their Twitter by Googling their Bandcamp username. Saw that they had tweeted twice in the past four hours:

cabbage_xo: virgos, man.

cabbage_xo: i love lesbians

I saw Nate for the last time approximately seven hours before he died. His skin was gray, taut to his skeleton, and his mouth hung open, sucking in breath with hard labor as his brain shut down his body piece by piece. The mobility of his left side had been stolen from him just weeks earlier, and the cancer had come to take the rest of it now.

When our grandmother died, I was so scared of her skeletal frame and her bulging, near-dead eyes that I wouldn’t even get close enough to her to say goodbye. I wasn’t going to make that mistake again.

It was nerve-wracking. I hadn’t spoken to him normally (or at all, really) since I’d left boarding school. We’d see each other sporadically as I grew up and out of adolescence; he’d text me periodically to give me updates on my former classmates who I hadn’t spoken to or seen in years. He’d tell me that my teachers, who had known me for all of six months, missed me. Mr. Bee sends his love, he’d told me. Ok. I replied. I don’t want it.

His wife hadn’t spoken to me at all since I’d arrived yesterday. She spoke to my sister who would then relay messages to me. Loop wouldn’t even look at me. I knew why she was angry, and I understood that there was nothing that I could do to correct that now. I thought back to my early childhood, before Nate and Loop were married. When he brought her home, all I wanted to do was be around her. I was obsessed with her, the way little girls flock to beautiful women in hopes that they will learn how to replicate their beauty. I wondered if someone told her, fifteen years ago, that she now hated the child she was once teaching to read, would she believe it? Would she believe any of it—the way that both of our briefly intersecting lives had turned out? I know I wouldn’t have.

Loop laid on Nate’s chest, curled up like a child. She was singing to him. It was the worst thing I’d ever seen. My brother, reduced to a body. His wife, reduced to a baby. I loved them both. I hated this moment.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered to him. Loop continued singing, softly, over my atonement. “I’m so sorry for everything.”

I don’t like to think about whether or not he could hear me, or what was lurking inside him during his final moments. I hope it wasn’t panic. I hope it wasn’t pain.

“I do not like this person,” Cashmere yelled at me. “And I really don’t get why you want to be friends with them.” Last week she’d met Cabbage for the first time on their birthday, when the three of us went out for a drink. It was a weird night. My period was so heavy that I wore an adult diaper, and I got so drunk off of dirty martinis that I announced that fact to both of them, provoking limited laughter. I don’t remember much else, except Cabbage and Cashmere getting into a spat because she and I wanted to get a cab home instead of going back to Cabbage’s place.

I smeared brown shadow across my eyelids, added glitter to the mix. I was trying new things out. I didn’t look like myself, but I didn’t look terrible, either. I contorted my face in the mirror; tested different expressions to see how my makeup behaved when paired with my range of facial movement. Okay, I thought, I am going to say something mean.

“Well, you don’t like any of my friends,” I said to her, still looking at myself in the mirror. “So that means very little to me.”

“This is different,” she was angry now, sitting on the edge of our bed and furiously typing on her laptop. She could have been sending a text, she could have been writing a paper. I didn’t get up to check, I didn’t ask—I just continued looking at my reflection. My self-obsession had become a major point of conflict over the past few years. Cashmere once threatened to leave me after I chemically burnt my eyebrows off with bleach, when I cried so hard about looking ‘ugly’ that my eyes swelled shut for days. I feel like you care more about your eyebrows than you do about me, she’d said. Your insecurity is cannibalizing this relationship.

“Why?” I said, turning to look at her. “Are you jealous of Cabbage?”

“What the fuck?” She looked up from her laptop. “No, I am not jealous of Cabbage. I think they are a bad person, and that there’s something very off about the way they talk to you. I don’t want you to get hurt.”

I felt stupid and cruel, and in a sense that was the hard truth of how I’d been acting. It didn’t occur to me that she could have been worried about me. Suddenly, my phone buzzed.

cabbage: i’m here and i’m double parked so get to the spot quick

“Have fun at the party,” she said. It was a departure from her previous tone. This statement was genuine, maybe even kind. And I felt evil, because there was no party.

Two days earlier, on a Thursday evening, I had been at a bar with Cabbage, stressed out and wounded by the trials of being a first year high school teacher. The kids were mean, my coworkers didn’t take me seriously, and worst of all, a bird shit on my blouse during lunch, and I spent the rest of the day in the same boxy school-pride shirt that the admin gives to girls when they’re out of dress code.

“I’m surprised you said yes,” they said to me. I’d previously declined all of their post-work drink requests. After my brother died, I smoked a ton of weed and drank almost every night, I’d told them. It’s a cycle I don’t really want to get back into. They nodded, told me they could relate, that addiction ran in their family, too.

That morning another teacher had worn a work-inappropriate outfit, and we’d had a staff meeting about it. I was so worried my clothes were the catalyst for this meeting, for no other reason than the shape of my body. I’d developed a busty figure toward the end of eighth grade, and spent my whole life since being told—by my mother and by teachers and by men who yelled out of car windows— that I could make a turtleneck look inappropriate because of it.

“It wasn’t about you,” they said. “You dress like a friar.”

“Yeah, but—” I laughed.

They finished my sentence: “Your rack.”

I felt heat creep into my face, somewhere between embarrassed and flattered. They leaned in to kiss me. I turned my head sharply, their lips hitting my cheek. It was open-mouthed and wet. I felt their tongue scrape my cheek.

“I think you’re cute,” Cabbage said once they pulled away.

“What?”

”I think you’re cute. And naïve. You’re the most insecure person I’ve ever met, and I don’t think you should be.” When I didn’t answer, they continued. “I know how hard it is to make friends around here. This place will kill you if you let it.”

I let their words stand plumb in the air. After a minute, I was speaking without realizing: “Can you just take me home?”

Then, more silence.

“I want to protect you,” they finally said. “From being alone.”

I walked out of my apartment, and when I was a block away from their car, Cabbage called me to tell me to hurry up because there were cops around. I ran into the street without looking, eliciting shouts and blaring horns. I’m sorry, I mouthed in the direction of the noise.

I noticed their outfit first. An orange, faux-patchwork buttoned shirt. Red pants, cuffed at the ankle. It didn’t match, and it was more color than I’d ever seen them wear. Stevie Wonder’s “Isn’t She Lovely” rattled the speakers. Cornball shit, was the phrase in my head. I couldn’t stop myself from thinking it.

“I’m trying to decide where to take you,” they said. The structure of this sentence was familiar. Throughout the weeks we’d known each other, whenever Cabbage spoke, they became subject, and I, object. “But I’m not going to take you there until you tell me why you have a crush on me.”

I texted them on the night that they tried to kiss me. I told them that I had a “big, idiot crush” on them—which, in part, was true. I liked the attention they showed me at the bar that night. And I really liked the version of them I’d seen in the articles and in the photos online. I didn’t have an answer for Cabbage now, though. I couldn’t tell them how I looked them up the day after we met, and that I liked their cultivated digital presence more than I liked the person sitting next to me now.

“I don’t want to tell you,” I said.

“Well, then, we’ll keep driving around until you do. And don’t try to get out,” they smiled. “This isn’t a safe place for walking.” It was funny, really. I hadn’t felt unsafe in the city at all until this moment.

“We can go tit-for-tat if that would take the burden off your tiny shoulders,” they continued speaking after minutes of nothing said. “You still need to go first, though.”

They turned the radio down in anticipation.

“This is all very Leo of you, you know,” I said.

“Avoiding the question is very Virgo of you.”

“I’m a Pisces.”

“All the Virgo in your chart overshadows that. Now, tell me why you like me.”

“Uh, the Adidas tracksuit that you wore to work last week was really sexy.” I thought it was so obviously a joke that it would be met with laughter, but I guess it wasn’t. They stayed silent, smirking to themselves.

“My turn,” they sighed. They seemed inconvenienced by the whole thing, as if it wasn’t their idea. “I think the forbidden aspect of this whole thing is hot as fuck.”

“Forbidden?” I laughed. I couldn’t help it. Cabbage wasn’t amused.

“I’m being serious. We probably shouldn’t advertise to the people at work that we went on a date.”

I told them I wouldn’t dream of it and pulled my knees to my chest. I looked up at them, watched the wind lift their hair from their scalp and carry it across their face. They pushed curls out of their eyes and wicked sweat off their forehead. The air that came in through the windows was hot and offered little relief from the car’s balmy climate. I brought my hand to my face and noticed makeup was slipping off my skin.

“Where are we going?” I asked. They didn’t answer.

For a while I couldn’t figure out why I always cried on my walk to the athletic center. Some time between August and now, it got to the point where I needed to call someone on my way from science class to gym class. Sometimes it was my mom, sometimes a friend—until I got caught with my phone and was reprimanded by a teacher I didn’t know, right there on the campus green in front of everyone. Now, phone-less, I would shut my eyes tight and count to myself as I made the trek across campus, tried to erase memory of that class before it even started. When you reach 50, I’d say to myself, you’ll open your eyes, and you’ll be in your dorm. Later, as an adult, I would worry that my entire life was imagined—an illusion created during one of these long blinks—and that I could, at any moment, open my eyes back up to find myself back at school. Sometimes this worry would evolve into fear, and I couldn’t keep myself from reaching my arms out, screaming for someone to stop me from being sucked back in time.

I was doing a pull-up when I first felt his hands on me. First on my lower back, and then on my inner thigh. Everybody was watching. Laughter came next. I dropped my pull-up and succumbed to the title of ‘shortest-ever hold.’ I’d look at the recorded time later, which was marked at less than three seconds.

“Was that weird?” I asked a classmate in the locker room, who shook her head in response. I pulled my shirt over my head, changed my shoes from my sneakers back to my heavy boots.

“My sister told me that Mr. Sea is just kind of like that,” she said. “You should just be grateful you’re not one of the boys. He hates most of them. When they come in for after-school gym hours, he’s just lurking around and waiting for them to fuck up so he can yell at them.”

“Wow,” I said.

“Yeah. That’s what’s weird.” she slammed her locker door closed, headed out into the hallway.

Thinking I was alone, I started singing to myself.

“Nice voice, Junior Jacklin.” I jumped, then pivoted. It was Sea.

“Oh,” I said. “Thank you.”

“It’s good you’ve got a talent somewhere in that little body. God knows athletics aren’t your strong suit.”

“I know,” I said. Then, emboldened with a bravery I hadn’t felt in a while: “You know my brother had me lie in my admissions interview. He told me to say I play lacrosse.”

“He told you to lie?”

I nodded. “And I didn’t even do it well. I thought lacrosse was the thing with horses…”

Sea laughed. Not a fake one, either. It was a real chuckle from the gut.

“I’m surprised they bought it.”

“Me too, dude.” I realized what I’d said as soon as it left my mouth, and pressed my lips together in preparation for backlash. I’d always had poor boundaries with authority figures—my siblings were so much older than me that I was used to being blasé with adults.

To my surprise, Sea didn’t reprimand my unusually casual language. He simply put his hand on my lower back again, started walking with me out of the locker room.

“JJ,” he called me. “Is there a reason you didn’t take the swim test with everyone else at the beginning of the semester?”

“I, uh,” I stuttered. “I was on my period.” It was a bad lie—I hadn’t even gotten my first period, didn’t yet understand the ins-and-outs of menstruation; I just knew that these were the right words to say to get a male teacher to leave you alone.

“See, that’s what I thought,” he said. “But then I looked at my notes. And that’s what you said to get out of it every time since, too. What’s the real reason, kid?”

I shed my pride, turned to face him, and said the truth: “I don’t have a swimsuit.”

He looked at me. His face dropped, his expression weighed down with the heavy mixture of pity and something worse. Something I couldn’t name.

“That can be our secret,” he winked, and once we were out of the locker room, we diverted. I watched him shrink into the distance until his form was swallowed up by the stone arches. I thought he would look back. He didn’t.

In the bar, Cabbage pressed their knees to mine as I drank two beers in ten minutes. They ordered for me, as they always did when we went to restaurants or bars. I hated the taste of the ones they’d gotten me. I didn’t like stouts, but they called that immature, so I drank them anyway.

We bar-hopped across town; talked about their life, listened to their chosen music on each jukebox, drove in their car, and then, all at once, I was far drunker than I should have been.

“Three and a half beers is good,” I mumbled. “I think I’m done.”

“One more stop,” they said. I didn’t want one more stop, but I was too focused on not throwing up to say anything.

It was the sketchiest of the four bars we had hit that night. The neon sign was cute though, a pink cartoon deer looking up through heavy eyelids. They held my arm, helped me walk up to the bar. Nobody else was there.

“Guinness,” they said. “Just the one, for her.”

We showed our IDs, and the bartender shrugged. She turned her back to us, and Cabbage put their hand first on my lower back, then on my inner thigh. I straightened my spine, shut my eyes. I wondered what this looked like from the outside, wondered why Cabbage waited for the bartender to look away.

“You like that?” They asked.

“Or something,” I answered. “I have to go to the bathroom.”

I stood up. I was scared and off-balance. The bartender pointed toward the bathroom which was, for some reason, outside of the bar, and then I realized that Cabbage and I weren’t the only people here after all. There was a group of women smoking weed near the entrance.

“You okay, sweetie?” one of them asked. Her face was fuzzy to me, but I could tell how stunning she was from the way she carried herself. Women don’t stand like that unless they’ve been aware of their beauty for a long time. Her nails, pointed blurs of red, grazed my skin as she rubbed my arm.

“Fine,” I said. “Just looking to piss.”

The beautiful woman pointed to the door behind her. Tears threatened to breach the confines of my waterline. I didn’t know why I was crying. The stall was so small that I couldn’t turn my body without hitting something. Every piece of jewelry I was wearing rattled as my ass crashed into the plastic seat. I held my hands to the walls. When I was a kid, my mom used to sing me some nursery rhyme about a skinny girl named Alice getting sucked down a bathtub drain, and I was scared that the toilet was going to do that to me now.

I looked down at my underwear. Beige, with torn edges from a year of weight gain. Oblong stains layered atop one another on the gusset. The elastic was loose and shredding. I ran my thumb across the frayed edge and felt the broken band poke my skin.

“You were in there for a while,” Cabbage said to me when I got back. I tripped getting into my seat, and they laughed. They would have never forgiven me for laughing at them. “Finish your beer,” they said.

“I can’t,” I protested, gesturing to my general drunken demeanor. “It’s too much.”

“We don’t waste beer,” they said. I was too fucked up to flout their rules. I wanted to ask them who we were, but instead, I put my elbows on top of the bar and rolled my head between the two points.

“Then you drink it,” I said, skull still tucked between my arms.

“No,” they said. Then, with more severity: “Finish it.”

So I did. This was my year of folly, I suppose—the one where I drink dark beer and try on adulthood like a light balm across my face; the one where I slip, fall, and flail toward endings that had been chosen for me.

I noticed Bee staring at me above the rim of his wine glass about three minutes before he realized that I’d caught him. I adjusted the strap on my dress, held eye contact with him, and waited for the wave of dropped faces and black clothing to mumble their sympathies and move on. He crossed the room to stand next to me.

“I wasn’t sure that was you until you spoke up there,” he said, leaning against the wall and not turning to look at me. “So different from the girl I knew.”

I couldn’t stop myself from laughing. He didn’t know me at all.

“That was a good speech,” he said when I didn’t answer him. “Great speech.”

I watched Cashmere across the room. Intently, the way Bee watched me. She was on her fifth glass of wine, arguing with her dad and talking with her hands. She was pissed, that much was certain, but I couldn’t tell why.

“So,” Bee turned to me. “How long has it been?”

“Almost seven years,” I said. “I graduate college this year.”

“My son does, too,” he sucked air through his teeth. “Do you remember my son? The one that’s your age.”

I nodded—I remembered Little Bee, but only vaguely. He was in my ecology class, loudmouthed and lanky. He had an older brother. Still living. I tapped my nails against the quarter-full glass I was holding, then threw the rest of the drink down my throat.

“Nate was a good man,” Bee said. “He talked about you a lot, even after you were gone.”

I choked, spit a bit of cabernet up in my mouth. I wanted to call him a name. Something mean and targeted to his insecurities, but I didn’t know him well enough, so I let the impulse fade.

“It’s his memorial. And you’re talking about me like I’m the dead one.”

He pushed a thin trail of breath out of his nose, punctuated it with soft laughter.

“How much have you had to drink?” He asked.

“Not enough,” I said.

“I’ll get you another,” he said. “Least I could do.”

Bee took the glass out of my hand, weaved his way through the crowd of mourners. I watched him pass Cashmere, whose argument with her father must have been escalating, because she threw her hands up in frustration and left the room. Her dad followed.

Bee placed the glass in my hand.

“Where are you going to school now?”

“Maine,” I said. “That woman, the one that just ran out of here, she’s my girlfriend. We go to school together.”

“That’s nice,” he smiled. “That you made the best of it.”

I tilted my head, bit my lip until I tasted metal, and sighed.

“Of what, exactly?” I asked. In my grief, I’d discovered a new favorite activity—asking hard questions of people who said stupid shit to me, and watching them flounder in response. Earlier in the month, a professor reached out to me to let me know I’d missed too many classes and was at risk of dropping a letter grade. Don’t care, I responded. My brother died last night. She avoided eye contact with me for the rest of the semester, and I finished her class with a near-perfect grade.

“Just of…well, you know. The whole thing. Of your circumstances.” He swallowed so loudly I could hear it, even over the noise. He tried to change the subject: “Do you play sports at your school? My son is on the crew team at Yale.”

I continued to stare at him.

“Crew,” he motioned like he was sculling. “Like rowing, you know?”

“I know,” I said. “I remember that boat shit from boarding school.”

“Ah,” Bee nodded. “That’s right, you do.”

I took another sip, swirled the liquid around until it was warm in my mouth; I let it wash over all of my teeth. I wanted all of them to get cavities. I wanted them all to get extracted. I wanted something to hurt worse than this.

“I know that your son got kicked out, too,” I said. “His senior year.” I knew what Bee was going to ask as soon as he opened his mouth, so I answered him before he could speak: “Nate told me.”

“Well,” he started. I felt the wine flood my face, loosen my tongue.

“Drugs, right? He was tripping balls, and he punched someone. Yeah, I remember. He punched Miss Key.” I set my glass on the table, looked at my knuckles. Except for the place where I had a wart burnt off in kindergarten, the skin was soft. I’d never punched anyone.

“It was unfortunate,” he quieted his voice, stared down at the floor.

“But he goes to Yale now,” I smiled, all of my teeth showing and violet-tinged. “That’s nice.”

Bee looked up and put his hand on my shoulder. I tried to shrug it off, but it stayed, anchored in place.

“It was so good to see you again. And…I really am so, so sorry about your brother.” His gaze, soft and lingering, told me what he was really apologizing for. He dropped his hand, turned his back, and he walked out of the room.

“Take your clothes off,” Cabbage said. They flicked the light on, and the last remnants of who I thought they were, the image of what I thought their room would be—dark and sterile, perhaps somewhat academic—collapsed in front of me. It was bright, like a doctor’s office, but it was decorated like a dorm: posters on the wall of basketball stars, supermodels in bikinis. Big Gulps laying sideways spilling orange liquid on the dresser. A maze of clothing in copious heaps on the ground, some in piles as tall as my knees. It stunk like a litter box, but there was no evidence of a cat. My foot caught on a stray belt. I stumbled.

I steadied myself in the middle of it all, and I took off my shirt. They pushed me onto their bed, sent my head crashing against the firm memory foam. I propped myself up on my elbows.

“Take it off,” they repeated, pointing to my bra. I was too drunk for the clasps, so I pulled it over my head, arms jerking like a dying animatronic. I hated my tits, which hung low on my chest and were dotted with acne scars. My areolas were pale and far too big for a woman who had never been pregnant, stray hairs springing up around the nipple. I placed my hand over my body. I didn’t want to be seen.

“I thought we were going to make out,” I mumbled. “Like we did in your car.”

“Then we would have stayed in the car.”

Cabbage unbuttoned my pants, began peeling me.

“Tell me if it’s too much,” they said, kneeling to the ground and pulling me by my ankles to the edge of the bed. I felt them reach inside me, press their fingers in until they wouldn’t go any further. They lowered their mouth, licked me raw. I felt the panic turn paralytic in my bloodstream, imagined the left side of myself sinking through the mattress; a body made waning moon—half of it elsewhere, searching for something more beautiful.

“Okay,” I slurred. “It hurts.”

They didn’t answer, only stood up and laid their body atop mine. I caught a glimpse of their erection; a pointed thumbprint, a small spear at risk of splitting the blue fabric of their underwear. I stuck my right hand in their hair and yanked hard. They grabbed my wrists and held them above me. Their hands were wet with blood.

“Let me just touch you,” Sea begged.

“What?”

Cabbage looked up at me, mouth red and eyes dark.

“I asked you to keep your hands to yourself.”

I awoke to all the lights on and the door open—and to the sounds of electricity running through the walls. I had only cursory memories of a hospital waiting room and the evidential IV bruises on my arms. I turned my head to the left and then to the right. My neck was stiff, and the ringing in my ears grew louder with movement. I forced my eyes, crusty and swollen, to open wider. I felt the stiff mattress beneath me. I ran my fingers across the floral wallpaper, picked the peeling spots with my nails. I was in a bedroom, one for a child, left with only flashes of how I’d gotten here.

Please don’t, I remember crying out. I’m scared of the dark. My lips were cracked. I ran my tongue over the raw divots, felt the sting radiate off of them. I heard footsteps, then the door moving.

It was the dean’s wife, Mrs. Flea. I knew she was a therapist, but she wasn’t the one I’d been seeing all year. I’d noticed her around campus, though. It was hard not to: she styled her white-blonde hair like a helmet, wore glasses so large that they eclipsed her face, and her mouth was so thin that her lipstick was only a straight, red line. She brought a chair with her and sat in front of me, smelling like overripe plums and an old folks’ home. I suppressed a gag.

“How are you?” She asked, and I wanted to laugh. What a stupid question.

“Not good,” I answered.

“I heard that you had a very rough night.”

“Where’s my therapist?” I asked.

“He’s unavailable.”

“I want my therapist.”

“And I want to talk about you,” Flea said, and I had half a mind to think she was mocking me. “Can you tell me what happened last night?”

“No,” I said. “And I’m not trying to be difficult. I can’t remember.”

She scribbled a few words across the pad of papers in her lap, and I tugged at my hair with both of my hands, like the memories would come loose if I pulled hard enough.

“I just took a few pills,” I continued. “I was having a nightmare. I was trying to sleep.”

“Yes,” she nodded. She dragged her chair forward with her foot until her face was too close to mine. Her breath, fishy and cat-like, smacked me with blunt force. “You did take some pills. Some Benadryl, a lot of Ibuprofen. Your roommate had a bottle of Midol, and you took some of that.”

“I was trying to sleep,” I repeated. “My head hurt, and I was trying to sleep.”

“Is that the case?” She was prying, prodding me like cattle toward answers I couldn’t give. I nodded. She wrote more notes. I tried to lean forward to see them, but she noticed and flipped to a blank page. There was more movement outside. I looked beyond the doorway, and noticed a police officer posted outside of the room. He had a gun in his belt.

“Am I in trouble?”

“No,” she answered quickly. “I’m just trying to understand how we got here. I saw in your file that you’ve been skipping gym class and track and field practice. I saw that you requested to transfer into…” she clicked her tongue. “Technical Theater. You went from Track and Field to Technical Theater. Is that right?”

“Yeah,” I said. “It was denied at first. I had to request the transfer twice.”

“And two days ago, your advisor informed you…” she flipped through her notebook, ignoring what I’d just said. “Ah. Miss Key informed you that you were several weeks behind on after-school gym hours. True or false?”

“True,” I answered. I pressed my spine to the wall and slid down until I was supine once more. I noticed a crack above us. I followed it from start to end, realizing the fracture traveled the entire length of the ceiling. I imagined the room collapsing, encasing the two of us in rubble. I wondered how long it would take to find our bodies beneath it all.

“You worried your roommate with those pills,” Flea said. “She called for help.”

I opened my mouth, but nothing came out.

“How long have you been feeling this way?” She put her hand over mine and gripped it. Her touch made me squirm, the way that tornado sirens used to; like something murderous was coming, something even my mom couldn’t protect me from.

“What way?”

“Well,” she took a long pause. “Suicidal, sweetie.”

I told her that I wasn’t. I asked if my brother knew where I was. She told me he did. She told me he had been the one to take me to the hospital. I remembered it now. The long drive across state lines to the closest emergency room. The depth of the color in the night sky—the silence, except for one brief conversation, when Nate asked me if I liked the local Chinese restaurant. I was confused, but I said yes, I love Egg Roll King, and he pointed out the window—a sign that said Egg Roll Queen. I wonder how she ended up so far away from her husband, he’d said. I laughed.

The nurse at the hospital tested my blood. She fumbled the insertion and blew my vein, didn’t even tend to the spill she caused. I watched it roll down my arm, the way children watch rain on car windows. I wondered what kind of hospital this was. She left with the vials, came back an hour later to tell us that a mistake had been made. There was nothing in my system at all.

At work on Monday, I floated through some version of routine: I made a pot of coffee in the lounge that I didn’t drink; I taught grammar while spelling restaurant as resteraunt on the chalkboard; I went to the supply closet just to stand in the dark and stare at the shelves.

I tucked myself away in my room during lunch. Feather drifted in, bringing a cloud of lemongrass essential oil with her. I was scared to look at her—I thought she would be able to see it oozing out of me. I kept my back to her, pretended to grade papers.

“Are you sick?” She asked.

I turned, cautiously, to face her. I asked her if she was speaking to me, and she looked at me like I was one of her students who needed reprimanding. I felt small and stupid. She gestured to my outfit.

“You’re wearing a sweater,” she said. “It’s August.”

“I run really cold,” I smiled, hoping she couldn’t see the sweat beads threatening to spill down my forehead. I was wearing Cashmere’s turtleneck, one I’d bought for myself a few years ago when I was smaller, then quietly slipped into her side of the closet when it wouldn’t fit me anymore. It strangled my chest, rubbed against me in all the wrong ways. This was the first time I’d worn it in years.

In the early hours of Sunday morning I came home, still drunk, and Cashmere was awake. I didn’t expect her to be. My limbs were heavy. Sore, even. I had lost my underwear and my left sock. I was wearing a different shirt than the one I left in.

I cleaned my face, changed into pajamas. While I undressed, I catalogued each mark. Handprints on my neck. A hickey on my jaw. A split lip. Cashmere spotted clusters of marks trailing my arms and legs that I hadn’t yet taken inventory of. She asked me what happened, and I told her some bullshit about falling down a flight of stairs. She knew I was lying, and neither of us cared.

I stared at my body in the mirror, stretched into different positions to see myself from all angles. The bruises on my thighs were the darkest. They were horrible and painful, but they looked just like wild violets. I pressed one. It turned white, then the color returned. I couldn’t care for live plants, but here was a garden, all my own, that I could wither and bloom at will.

“Do we have any Gatorade?” I asked.

She told me we didn’t.

Feather left the room without asking any other questions. I felt blood start to trickle out of my vagina, and I took a sharp breath. That morning, I went to the bathroom as soon as I got to work, where I discovered blood pooling in my underwear. It was so much that I worried that I’d been eviscerated—scared I’d look down to see my guts sputtering out of a jagged wound across my thigh.

But I hadn’t been cut at all. The blood was dark. It was no puncture, this was an excavation: Cabbage the coal miner, the pearl diver, the grave digger. I cried quietly—balled up toilet paper and stuck it in my mouth to keep sound from escaping. I bent forward and screamed. I wanted to leave. I wanted my mom. I wanted to walk out of the bathroom and find myself back in Mt. Vernon, steps away from my childhood home. I wanted the porch light to flick on.

I heard a soft knock on my classroom door. I crossed my legs to suppress the bleeding and forced my lips to curl upwards into a patient, docile smile.

“Hey,” Cabbage said.

I took a long blink, removed my glasses so their face would be blurred when I opened my eyes. I didn’t want to see their teeth.

“Do you want to get drinks after work?” they asked.

I said yes. There was no hesitation.

me: motherfucker i cannot stop thinking about you.

I texted Nate’s phone number, which was now dead as he was, and watched the message bubble turn from blue to green as it sent. I lay in bed and tried again, over and over until the errors piled up, and none of them were even trying to deliver anymore.

me: i hate you so much.

me: i didn’t mean it

me: sorry

me: i’m just so angry that i lost you twice.

I closed my phone, then opened it once more. I’d bookmarked Nate’s obituary, and would read it repeatedly in the quiet moments. By now, I could shut my eyes, cover them with my palms, and recite the first hundred words like The Shema: Nathanial Scott “Nate” Jacklin, 45, of Williamsburg, Virginia, passed away on November 15th…

It was poorly written, and that pissed me off, but that didn’t stop me from going back to it every night. It was painful. I wanted it that way. I liked combing through the comments, reading the stories from all phases of his too-short life. I learned about him through these blurbs—how in college, they called him “Nate Dogg,” how he was the “sweetest little boy” growing up in Mt. Vernon. I wanted to call him, ask him questions about every story, but I couldn’t. So I searched his name again.

I found another obituary, this one published in the boarding school’s alumni magazine. This one was polished, a sanitized version of his life meant to be read by people with hearts to be touched, then inevitably, money to donate. There was little mention of his life outside the confines of that place. If he hadn’t completed his high school education here, it read, it’s likely he would have remained in small town Ohio for the rest of his life. I tasted bile in my mouth.

I pictured myself in a casket—my hands made wax and my jaw wired shut. I imagined the school reducing me to my life while I was there, trying to sell me to donors postmortem. If she hadn’t started her high school education here, it might read, it’s likely she would have been fine.

I’d never been more alone in my life. But my life was still mine, at least. And the world was still real. I looked out the window, saw the snow falling down on the cars outside. They were in their nascent stage of being buried. Come morning, the people would return and scrape the hardened chunks off the windshields. They’d turn the snow to sludge with their boots and their tires. But I’d sit here and wait for the good ending. I’d watch the sun break into the sky, watch the daytime spill over all of it. The cars. The snow. The ground beneath. Everything licked clean by the violet light.